Springtime in the northern hemisphere means beautiful, clear, sunny spring days, but these same cloudless days can lead to the perfect conditions for significant frost risk at night. Overall, frost negatively impacts quantity more than quality and can be an annual event in cool regions like Champagne and Niagara, but it can also impact warmer regions like Bordeaux and Napa. A frost that gripped France in April of 2017 caused losses of 20-50% in Champagne, and its impact reached all the way down to Languedoc and Roussillon. Understanding frost and its prevention are important to the economic survival of many vineyards around the world.

What is frost?

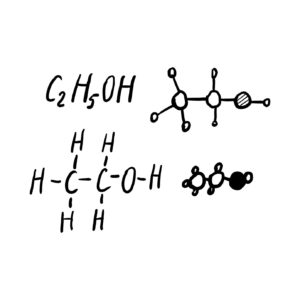

Frost is a deposit of ice crystals when temperatures fall below freezing (0°C). Frost damage occurs in a vineyard after the green tissue has started to swell with moisture after budburst as this moisture is subject to freeze. There are two types of frost in the vineyard: advection frost and radiation frost.

Advection is less common as it is a large mass of cold air that settles on a large area. This type of frost is more common in the winter season where it can occur both during the day and night. This is a difficult kind of frost to protect against since there is no warm air to be circulated.

Radiation frost is more common and occurs on cold, still, cloudless nights. Note that soil generally absorbs heat from the sun during the day and releases it at night, helping to warm vines. Also note that warmer air rises while colder air will sink toward the ground, and clouds can stop warm air from rising higher, helping moderate night temperatures. Therefore, on cold, still, cloudless nights, warmer air will continually rise through the atmosphere, and ground air will become colder and colder.

When does frost occur?

Frost damage occurs most commonly in the spring after budburst when green tissues (including leaves and embryonic flowers) have started to grow. This tender tissue is swollen with water that will freeze. Dormant vines and older growth have less moisture and are thus more naturally protected. Spring frosts can kill off this young growth and cause a loss of quantity and damage the forming buds of next year’s growing season. Quality is generally not impacted by spring frost except that ripeness may be less uniform and canopy management more complicated.

Frost damage can occur before harvest in the autumn as well. While a less common occurrence if the variety is well-matched to the site, freezing grapes can rupture (reducing weight/quantity) and provide an entry point for disease development and fungus (decreasing quality). An early autumn frost can also cause leaves to drop faster, impacting carbohydrate accumulation, which will have a negative impact on the winter hardiness of the vine.

Frost prevention

There are passive and active strategies that can be used to help mitigate the risk of frost in a vineyard. Passive strategies that start before the frost season include site selection, ground cover management, cordon height, and delaying budburst. Active strategies include using water sprinklers, wind machines, and heat when frost is about to strike.

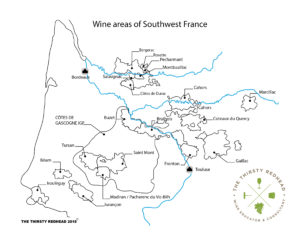

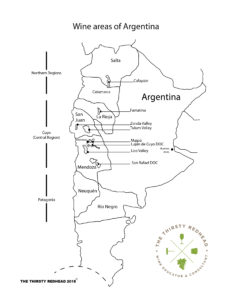

Site selection would be the first way to help prevent frost risk. While not always possible, an ideal scenario would be to plant in an area with low frost risk like Sardinia, Italy or Worcester, South Africa. If that’s not possible, planting near large bodies of water will help temper the local climate and mitigate frost risk. For example, the vineyards in the Finger Lakes grow on a narrow band along the shores of these lakes to benefit from their tempering effect.

Within a site, planting on a slope can mitigate frost risk as cold air moves to lower ground like water. One vineyard in the Finger Lakes had a small depression in a vineyard that pooled cold air and was planted to Pinot Noir. Due to the freezing of the vines in that small dip every year, that patch is now planted to Riesling, which buds later.

Vineyard floor management can help mitigate frost risk. A flat and clear vineyard floor will absorb and release more heat than one covered with an insulating layer of cover crops or mulch. Soil moisture will also absorb more of the sun’s heat than dry soils.

Since cold air stays close the ground, the cordon height is another way to mitigate frost risk by planting higher as is done in the Alto Adige in the northeast alpine region of Italy.

See? Apical buds (the ones at the ends) burst before the basal buds (the ones closest to the trunk).

Delaying budburst—keeping the vine closer to the dormant stage until frost risk has passed—is another strategy. A vineyard manager can start by planting a late-budding grape like Riesling (relative to Pinot Noir in the example above). That said, the vine still needs to be matched to the growing season of the area. Cabernet Sauvignon is also a late-budding variety but needs a long growing season and will not sufficiently ripen in a cool climate like the Finger Lakes.

Pushing back winter pruning while the vine is still dormant will generally not delay budburst, but double pruning can help. This strategy uses winter pruning to remove excess growth and leave this year’s fruiting wood with a full complement of buds (30+). Since buds on the tips of canes will burst first (and basal buds last), leaving the full amount of buds during the frost season will make those buds subject to damage before the basal buds have started to swell. After frost risk has passed, the canes (with the useless buds on the ends) will be pruned away, and the basal buds will then burst without risk of frost damage. This double pruning method is very labor intensive but has been shown not to delay harvest dates.

Strategies that can be used after vineyard establishment include using overhead sprinklers as frozen water will not drop below 0°C, thus protecting the tender shoots in a “blanket” of frozen water.

Wind machines are common in many vineyards around the world and work by mixing the warmer air above with the colder air below, moderating the overall temperature of the vineyard. Some parts of the world use helicopters to mix air on the same principle. While wind machines are more common where frost in an annual event, helicopters can be used when needed and can target the areas that are most at risk.

Heating a vineyard via smudge pots, burning winter pruning, or bougie candles warm the air via convection. This method needs multiple sources of heat throughout the vineyard and would work best if there was an inversion layer to trap the heat being generated (which is often not present).

Less conventional methods to help with frost risk include heated wires wrapped around the cordons and canes. This has been shown to be reasonably effective, though it does not cover and protect the whole canopy.

Artificial fogging can also create that needed inversion layer to trap cold air, but a vineyard would need a very clean source of water and a fine emitter to produce this result. There is also a risk of public liability if the artificial fog were to spill into roadways.

Conclusion

With frost damage making the headlines more often in more grape growing regions, understanding how frost is created and employing the right mix of prevention and mitigation strategies are more important than ever to help bring in a complete, uniformly ripe grape crop.