If you already have some wine knowledge under your belt and are ready to take your education of wines from Italy to the next level, I highly recommend pursuing the Italian Wine Professional certification program, proctored by Italian Wine Central.

First, be sure to check out Italian Wine Central’s amazing website. It’s really easy to navigate, it has fantastic (and consistent) maps and I can always find a quick answer to whatever I’m researching. Go bookmark it now.

On to the course!

What is the Italian Wine Professional?

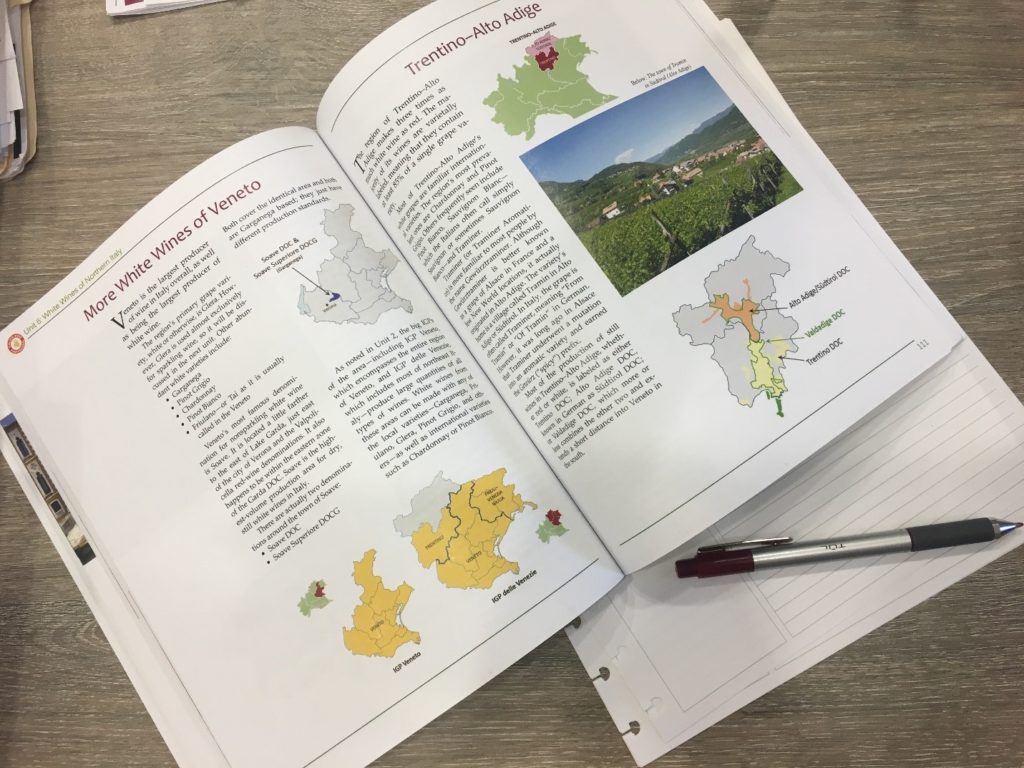

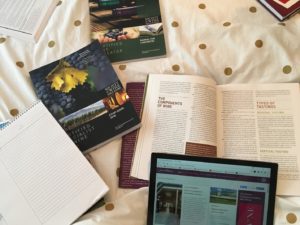

The Italian Wine Professional is the second of two levels in Italian Wine Central’s education program, which is made available online several times a year (via Napa Valley Wine Academy). Once you register for the course, you’ll receive a physical textbook and join an online group where you can access eight weekly webinars and discuss the lessons with your classmates. The course is self-paced, but the weekly webinars and regular reminders will keep you on track. There is no required tasting portion (bummer, but I took the online course), but they do have flights that they recommend for each of the eight units that are commercially relevant.

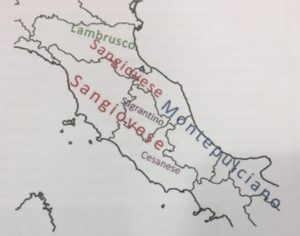

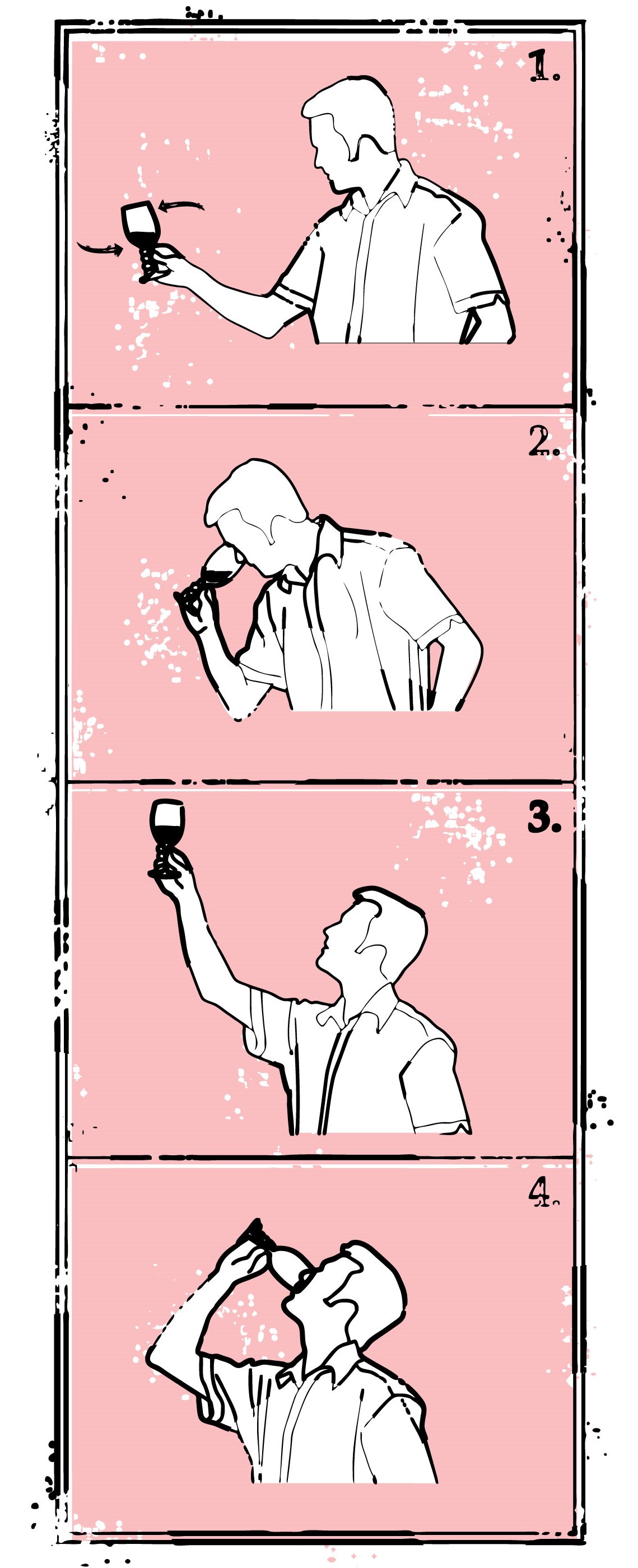

The final exam is an online 100-question test comprising a mix of multiple-choice questions, map identification questions, and a very tricky yet useful exercise in which you’ll have to correct the mistakes in an Italian wine list—wrong section, DOC versus DOCG, incorrect grape, appellation typos, etc. In addition to the exam, you have the option to put together a presentation on any topic from a given list to improve your grade (I planned to do this myself, but time is never on my side).

What does the course entail?

First, let me tell you my favorite thing about the course: instead of studying wines region by region, the lessons are laid out by wine style, which makes much more sense. After a brief introduction to Italy, reds are covered first by northern, central, and southern regions, followed by whites in the same fashion. Finally, sparkling wines are covered in a separate section as well as baller wines (or luxury wines, as they’re called in the book).

This is by far the most logical way to study Italian wines. I’m also impressed that the course creators combined premium wines into their own group, because that’s naturally how your potential buyer would think of them. With those out of the way, it’s easier to focus on understanding the diversity of other DOC/Gs that usually stand in the shadow of these classics.

Aside from the excellent curriculum, another plus of this course is the fact that you can check your progress with quizzes in the book. The online portion of the course basically repeats the text from the book, although quizzes are included throughout each section to ensure you retain the information and get a feel for the types of questions you’ll see in the final exam.

The only flaw I found was in the online exam provider, ProctorU: I finished my exam only to have the screen freeze, forcing me to start the exam over. The live proctor wasn’t sure if my score had been saved or not, so I had to wait a few days to find out if it had even registered my test. Needless to say, I didn’t need that kind of stress after cramming for the last few days!

Should I take this course?

If you’re passionate about Italian wine, then yes! The Italian Wine Professional course offers a challenging yet logical way to learn about Italian wine, so it will certainly be worth your time should you choose to pursue it.

I’m currently enrolled in the Italian Wine Scholar program by Wine Scholar Guild, which goes into the minutia of wine on a traditional region-by-region basis, so having this solid foundation of knowledge from the Italian Wine Professional makes this one easier to follow.

I recommend this course for wine professionals or enthusiasts who already have a strong background in various wines of the world, such as those above WSET Level 2. So if you really love Italian wine, be sure to check out the Italian Wine Professional certification program today!